The Family of Franz Ledermann.

From the series “Jewish History in the Lützow Quarter”, by Prof. Dr. Paul Enck, www.paul-enck.com. Part One.

On the occasion of the memorial ceremony and the laying of Stolpersteine on Genthinerstraße on 8 September 2022 for members of the Ledermann–Citroen–Philippi family, who became victims of National Socialism, both the opportunity and the necessity arose to supplement the little that was previously known about the family’s history through some additional research. The only survivor, the now 97-year-old Barbara Ledermann Rodbell, left her Berlin home as an eight-year-old girl and took only a few memories with her. As Sarah Richardson, her granddaughter, expressed it in her address at the memorial ceremony: “One of the tragedies of losing these people and their possessions is that the information we have about the Ledermann, Citroen, and Philippi families in Berlin is minimal and incomplete.”

In the end, however, the collected information that we present here in a total of five parts is only a pale substitute for the many lost lives.

The Genealogy of the Family of Franz Anton Ledermann.

Genealogy forums on the internet contain a number of family trees of families with the surname Ledermann, but they do not always agree on the lineage from which Franz Ledermann, who was born on 16 October 1889 in Hirschberg and died in Auschwitz in 1943, descended. And then there is the personnel file of Dr. Franz Ledermann in the Reich Ministry of Justice (archived in the Federal Archives in Berlin-Lichterfelde, containing his own information about his origins, which makes it clear that all of them were and are mistaken. The following information is therefore based on the details in that file. It also documents his entire legal education and professional career between 1912 and 1933 and forms the basis for many further insights.

Franz’s father, that much is certain, was Benjamin Benno Ledermann, born on 4 March 1847 in Ostrow (today: Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland), approx. 100 km northeast of Breslau (today: Wroclaw) and 180 km west of Lódz, and who died on 18 June 1911 in Breslau. He was a highly respected lawyer and judicial counsellor in Hirschberg in the Giant Mountains, actively involved in various Jewish community boards and charitable organizations, and his death was deeply mourned by the local Jewish community. The further paternal lineage was less clear: in a 1933 questionnaire, Franz Ledermann stated that his grandfather was a certain Gerson Ledermann, a religious official from Ostrowo who died in Wroclaw. There was no information in the file about his wife. Franz also noted that his great-grandfather had been naturalized in 1828, without providing names or details.

Ostrów in the Prussian Province of Posen

According to the lists of Jewish citizens in the Prussian province of Posen, based on the 1833 census and who had received naturalization patents at that time, there were three naturalized families in Ostrów with the name Ledermann:

Ledermann Hieronimus, fishmonger (naturalized on 9 July 1834);

Ledermann Meyer, hat maker (28 April 1834);

Ledermann Wolff, small trader (9 July 1834).

There were additional naturalized families with this name in other districts of Posen, such as in Graetz (Ledermann Hirsch, merchant, 11 September 1834; Ledermann Moses, merchant, 11 September 1834) and Kempen (Ledermann Isaac, merchant, 21 August 1834). Families who were not naturalized but merely tolerated were not listed by name. These lists were already published in 1836; the reprint of the lists in 1987 contains no additional information.

Naturalization meant the legal equalization of Jews with the non-Jewish German or Polish population, though still with significant restrictions (no freedom to practice a trade, no military service), whereas “toleration” conferred no civil rights at all and could lead to expulsion at any time.

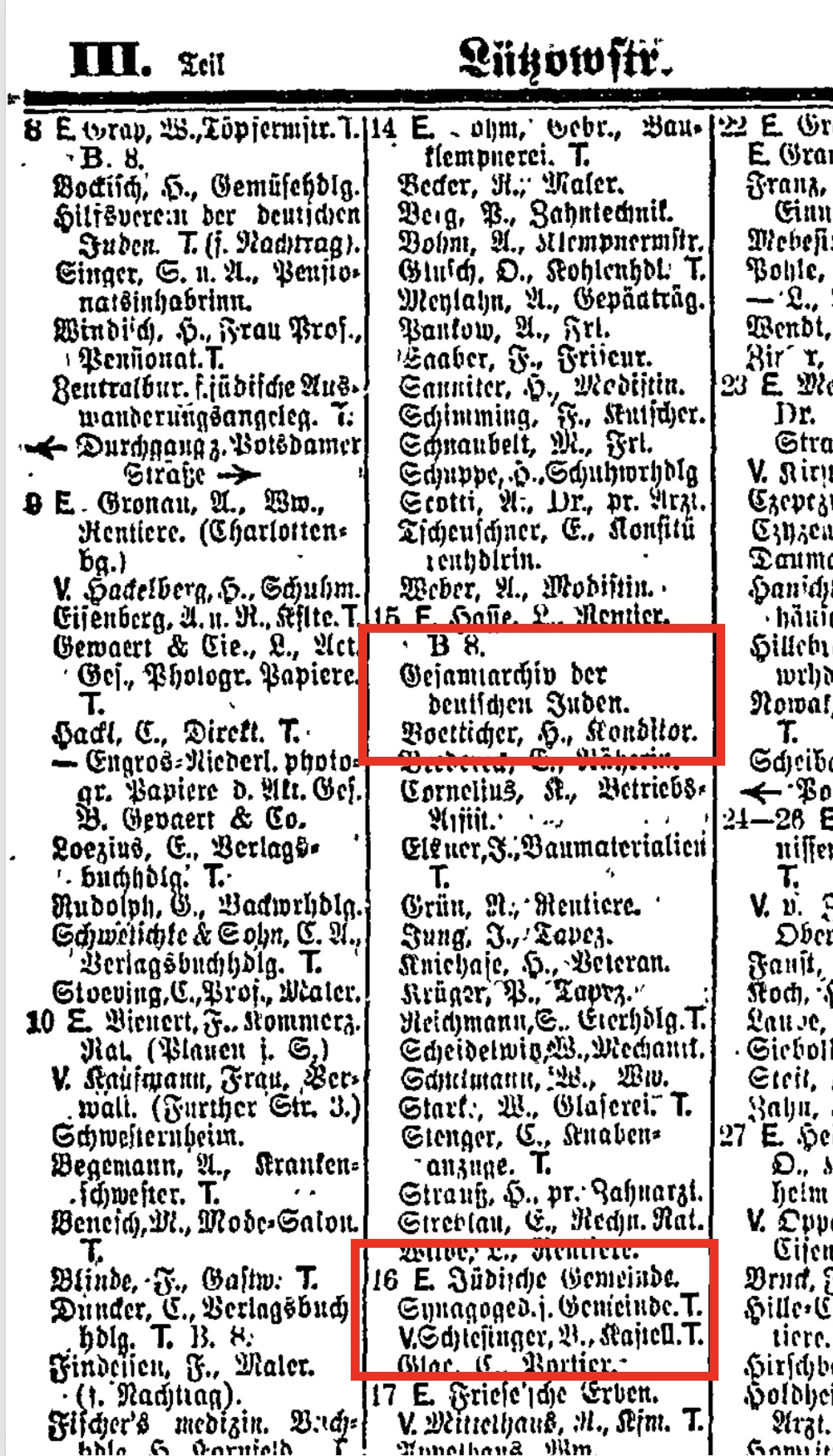

Fortunately, original documents from Ostrów survived because the community had already handed over its records in 1906 to the Central Archive of German Jews, which at that time was located in Berlin at Lützowstr. 15. It remained there until 1910, after which the archive moved to Oranienburger Str. 26. The documents reached the Center for Jewish History (CJH) in New York in time to escape destruction during the Second World War. The CJH in New York digitized the materials and made them available online — these documents have been used for the account that follows and are referred to here as the “Ostrów Files.”

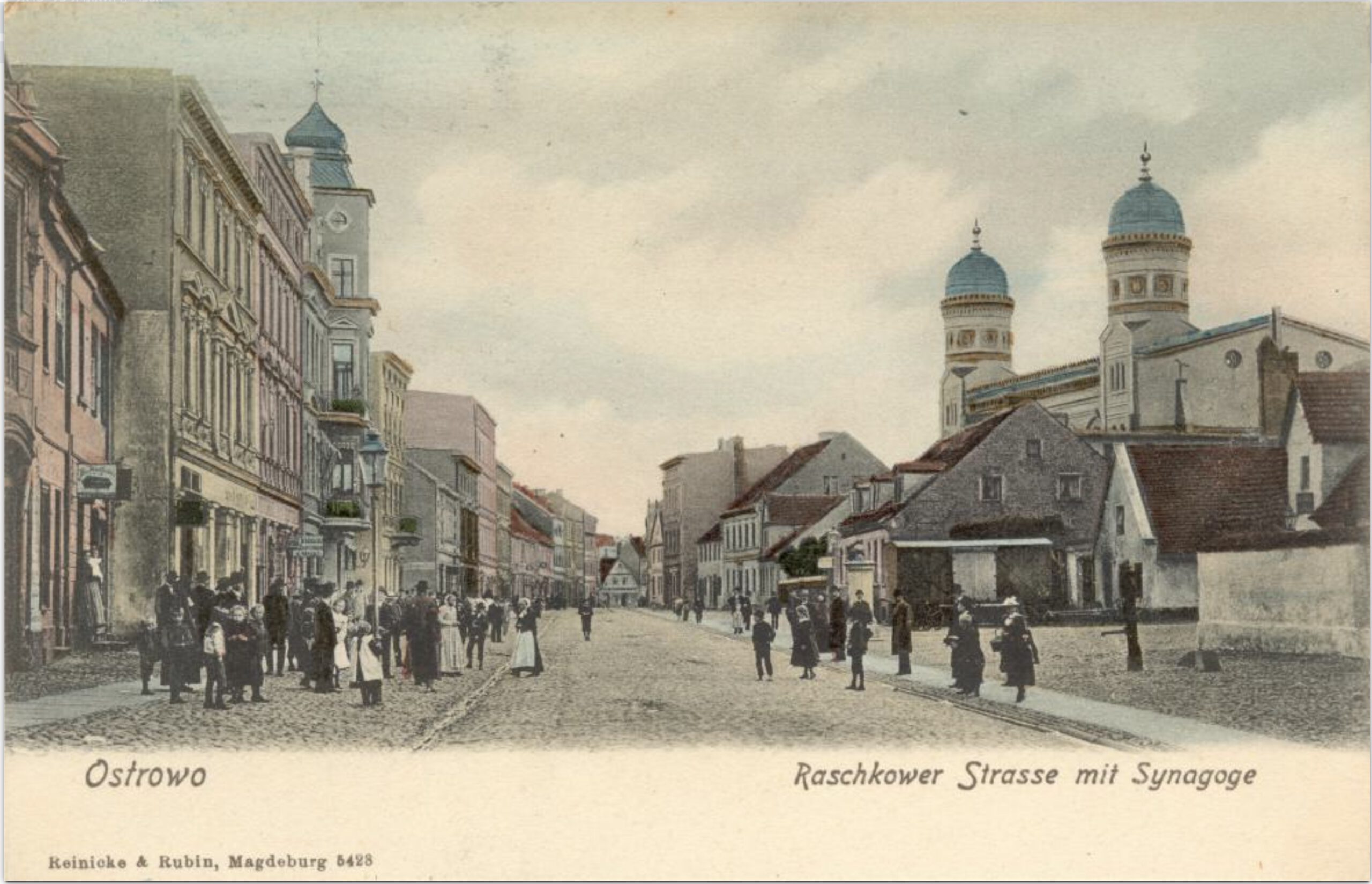

The Jewish population of Ostrów rose steadily between 1776 (156 persons) and 1861 (1,900 persons), only to decline steadily in the following years, reaching just 49 persons by 1931. According to Freimann, who in 1896 evaluated the community’s documents from 1848 (?), there was only one of a total of 157 families whose head of household was a Marcus Ledermann — this may refer to the Meyer Ledermann mentioned above. But this quite obviously relates to incomplete records, such as the naturalization list of that year. In the local documents referred to as the “Ostrów Files,” which were submitted to the Archive for Jewish History in Berlin, there were around the year 1845 three families in Ostrów bearing the name Ledermann who could be considered as the family of origin of the father of Franz Ledermann, Benjamin Benno Ledermann (born 4 March 1847). All three heads of household signed a letter dated 30 March 1841 concerning “the undersigned heads of families regarding the abolition of the ban on private instruction in Jewish religious teachings according to the prayer liturgy”, namely hat maker M(eyer) Ledermann, merchant J(oseph) Gerson Ledermann, and furrier G(erson) Selig Ledermann. It took some time and effort before we were finally (in October 2022) certain that the grandfather sought — Franz Ledermann’s grandfather — was Joseph Gerson Ledermann.

The Grandfather: Joseph Gerson Ledermann

Joseph Gerson Ledermann was presumably born in 1802 in Ostrów, but information about his parents is imprecise: they may have been Heymann Heimann Ledermann and his wife Feigele (or Vögele or Vogel) from Ostrów, but this has not yet been confirmed.

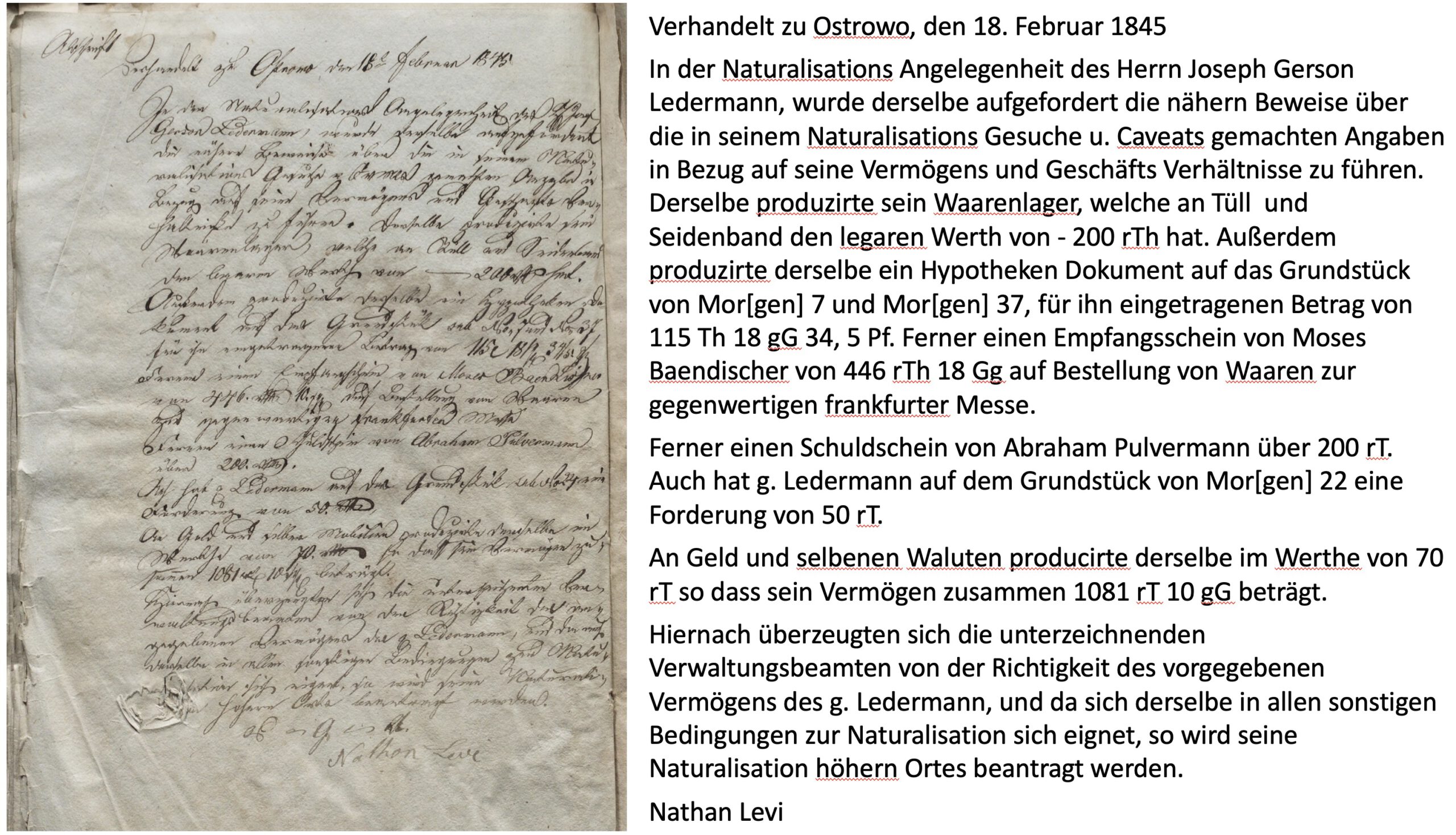

Joseph Gerson Ledermann received his toleration certificate (No. 24) on 13 November 1834, which was renewed in 1835, 1837, 1838, 1839, 1842, and 1845. In 1838 he applied for the issuance of a naturalization patent, but he did not receive it until seven years later, dated 18 February 1845. His occupation at that time was “merchant.” When he was naturalized in 1845, it was noted that he operated a shop selling silk ribbons and tulle, that he also visited neighboring markets, and that he paid 4 thalers of business tax annually. His assets were valued at more than 1,000 thalers, and he was able to demonstrate this in a scheduled hearing.

He was still unmarried according to the 1837 toleration certificate, but in 1838 he married Bertha Lissner, daughter of merchant Hirsch Lissner of Ostrów (naturalized there on 28 June 1834) and his wife Brafin, whose maiden name is unknown. According to the toleration certificates from 1839 to 1842, the family had one child; for the year 1842 it was noted that a child (Dorchen) had died on 11 May 1841, and that a daughter (Bane) had been born on 29 November 1844. And at the time of his naturalization in 1845, the family still consisted of him, his wife, and one daughter. In the years that followed, he no longer appears in the Ostrów documents; neither is the birth of Benno recorded there, nor do the Ledermanns appear elsewhere in the community records — not even in the contracts allocating the seats in the synagogue built in 1860. However, the contract with merchant Lissner, his father-in-law, is indeed found there. It is therefore likely that the family had already left Ostrów. Benjamin Benno was born on 4 March 1847, although we know this not from the Ostrów Files but from his son Franz; no additional children are known so far.

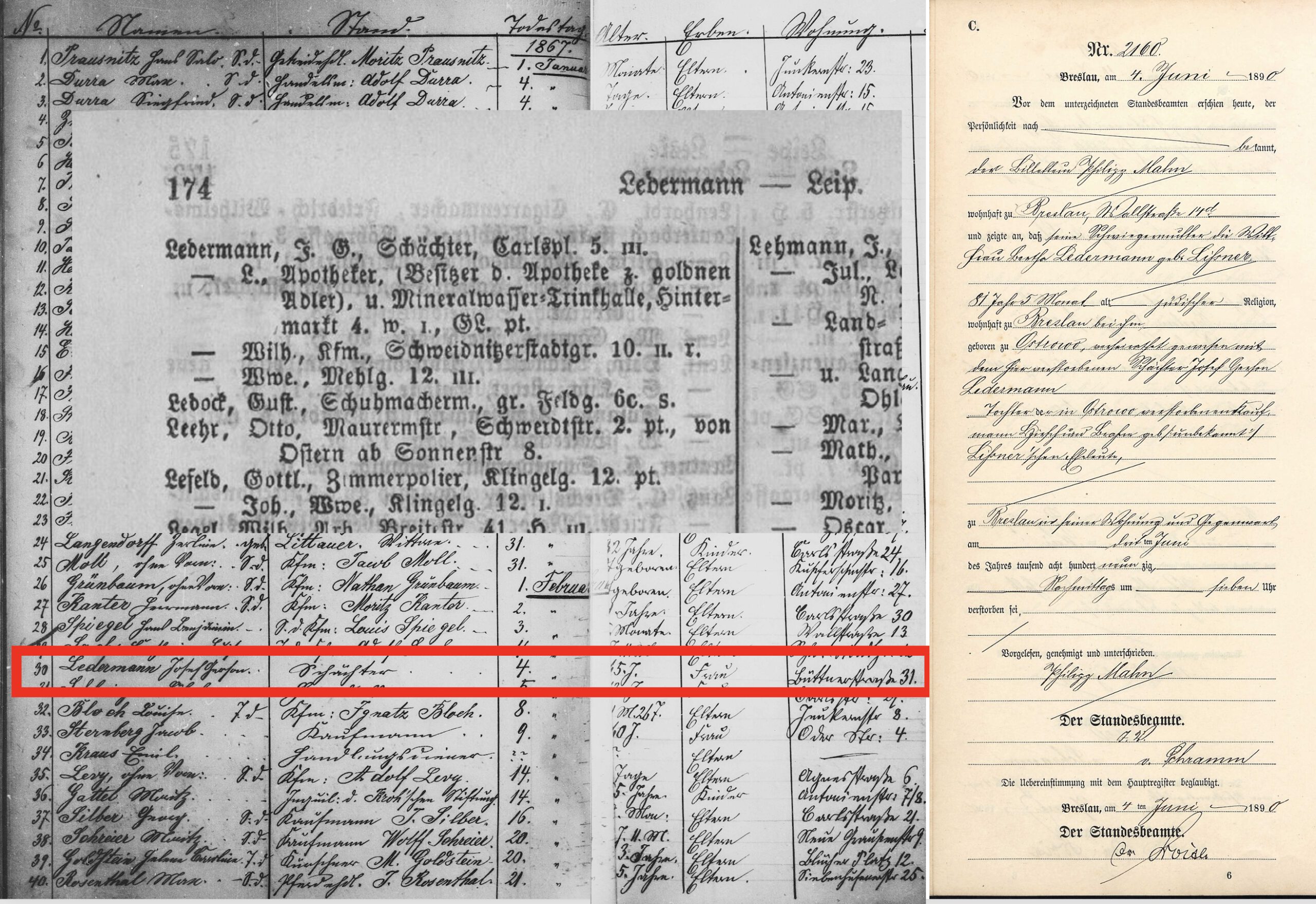

Exactly when the family left Ostrów is unknown, but in doing so they followed many families who emigrated from Posen after naturalization (or because it had been refused). After all, this was one of the purposes of naturalization: the relative freedom to choose one’s place of residence. Families moved to Berlin, to Silesia — especially to Breslau — to the Prussian heartland, or directly abroad. In the 1853 address book of Breslau, there is still no Ledermann family listed in the city, but years later (1862, 1864), Joseph Gerson Ledermann, now working as a shochet (ritual slaughterer), is living in Breslau at Carlsplatz 4. Meanwhile (from 1860 onward), his son Benjamin is attending the Breslau Gymnasium, where he completed his Abitur in 1868. Where the family lived between about 1846 and 1860 is not yet known. While Joseph Gerson Ledermann did not live to witness the social rise of his family, his wife Bertha was able to witness the successful professional path of their son Benno Benjamin, his marriage, and the birth of three grandchildren in their new homeland of Silesia.

Joseph Gerson Ledermann died in Breslau on 4 February 1867 at the age of 65. His wife Bertha died many years later, on 3 June 1890, also in Breslau, at the age of 81 years and 5 months, and was thus probably born in January 1809. Philipp Mahn of Breslau registered the death of his mother-in-law in 1890, so his wife must therefore have been their daughter Bane.

Excerpt from the 1909 Berlin address book. Marked at Lützowstrasse 15 is the Central Archive of German Jews next to the Lützowstrasse 16 synagogue.

Scan of the naturalization patent for Joseph Gerson Ledermann (naturalization list for 1845) from the Ostrów Files

Scan of the transcript of the hearing with Joseph Gerson Ledermann on 18 February 1845 from the Ostrów Files, as well as a transcription of the text.

Colorized photograph of the synagogue of Ostrów (built in 1861), around 1910 (postcard, public domain).

Excerpt from the 1862 Breslau address book, the list of deaths of the Jewish community of Breslau from 1867, and the civil registry death certificate from Breslau from 1890.

weggum.com

Source: https://www.juele.eu/