PICTURES.

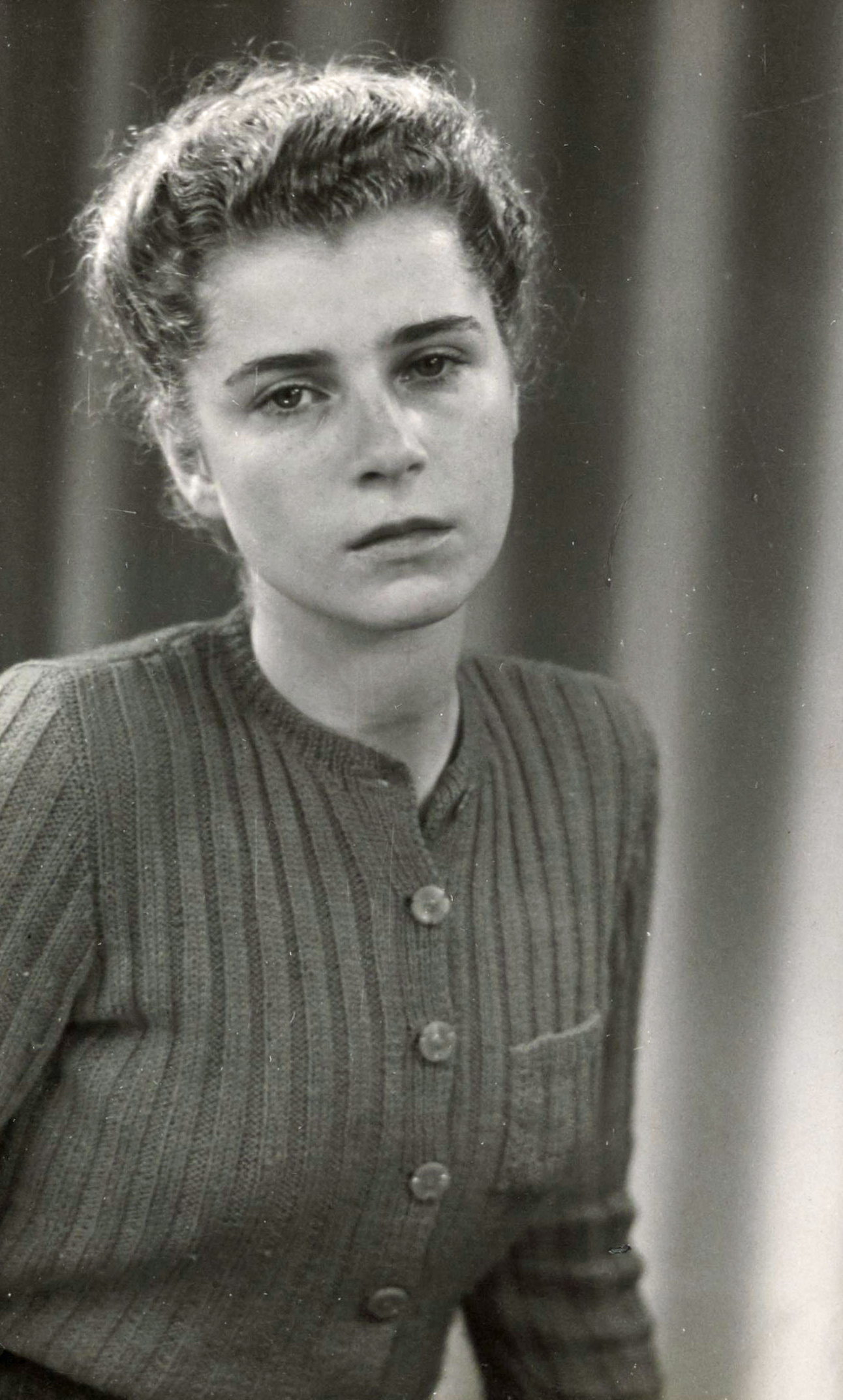

On the backside of this picture it says that it was made in 1944, this is written by hand, probably by Barbara herself. The name of the photographer is also printed on it:

FOTO Bart de Kok

studio Eldek

Vijzelgracht 27, Amsterdam

Tel. 33734.

This Lambertus Jasper de Kok:

FOTO Bart de Kok

studio Eldek

Vijzelgracht 27, Amsterdam

Tel. 33734.

This Lambertus Jasper de Kok:

He was a collaborator during the war and was sentenced to .. years in prison. It is odd that Barbara had made her picture by him.

Lambertus Jasper (Bart) de Kok (Nijmegen, 6 September 1896 – 1972) was a Dutch photographer who worked during the Second World War. De Kok was a member of the NSB (National Socialist Movement) and took photographs of major and minor political events on behalf of the German occupying forces and the Amsterdam detective Willem Klarenbeek, which allowed him to photograph subjects forbidden to other photographers.

De Kok made a second print of every photograph without permission and stored these in the house of his acquaintance Joseph van Poppel in Amsterdam-Zuid. After the war, De Kok and Van Poppel were interrogated and the house was searched, but the photographs were not found. Photos that De Kok took in 1943 at Muiderpoort Station of a transport of Jews did become known. In 2010, during a renovation of the house in Amsterdam-Zuid, 250 of De Kok’s photographs were discovered, which he had taken in 1941 and 1942. These photographs show a confrontation during the February Strike, the removal of street name signs from streets with names of Jewish origin, and the seizure of diamonds from the mostly Jewish traders in the Diamond Exchange on 17 April 1942.

Sometime in 1941, Van Poppel introduced Bart de Kok to the Beauftragte für die Presse Boijes. Boijes instructed De Kok to take photographs of “all political events”: processions of the WA (the violent “order service” of the NSB) and scuffles between WA members and members of the Nederlandsche Unie. However, De Kok also took photographs at the request of a detective with the Amsterdam police, who had been seconded to the Crisis Control Service (CCD): Willem Klarenbeek. This man had himself photographed while frisking Jewish diamond traders, arresting Jews and taking them to the station on Doelenstraat, and rounding up Jews for the illegal slaughter of sheep and cows. As far as is known, Klarenbeek is the only “rogue” detective who had himself extensively photographed during his work.

De Kok received 50 cents per photo. He felt this was too little, but Boijes had told him that it was his duty as an NSB member to cooperate. He had to hand in the negatives, including those of the photos he did not sell to the Germans—undoubtedly without informing the occupier. What Boijes did not know was that De Kok delivered a print of every photo he took to Joseph van Poppel as well, including those he did not sell to the occupier. Presumably, therefore, there were three sets of photos: the ones found in De Kok’s home, the ones De Kok gave to Boijes, and the photos hidden by Joseph van Poppel, which have now been discovered in the building in Amsterdam-Zuid. What Van Poppel intended to do with the photos is unknown.

In total, De Kok took hundreds of photos. A limited number of these were already known, as noted above, such as a previously published photo of a CCD raid on the café of Wolf Hartlooper at Nieuwmarkt 15. New, however, are several photos of that same incident that were rejected by De Kok, presumably for photographic reasons. The other photos have not been published before. Altogether, the collection comprises some 250 photos, taken at dozens of (political) events.

In 1943, the occupier no longer had work for De Kok, he stated during an interrogation after the war. “I did this photographing until 1943. Then Boijes left for The Hague, and with that my work ended.”

In late 1944, De Kok, as an NSB member, received a compulsory call-up for the Landwacht (auxiliary police). He went to Zutphen for railway line surveillance and later to Harderwijk for the same work. No “atrocities” by De Kok are known from this period. It did emerge, however, that early in the war he had been sentenced by a German court to a fine of 100 guilders because he had lent a firearm to his “good” NSB friend Frans van Dam, who had committed a murder with it in the Amsterdamse Bos in “late 1941.” In April 1944, De Kok’s company was ordered to report to the SS, but he did not go. After the company was disbanded, he went to Amsterdam, but felt “outlawed” there as liberation approached. He then wandered around the Netherlands, in Utrecht, Hilversum, and The Hague, where he was arrested in July 1945 and interned in the Grand Hotel in Scheveningen.

In December 1945, De Kok was transferred to Amsterdam. The interrogations then revealed that De Kok had also worked for the Abwehr, the occupier’s counterintelligence service. De Kok photographed Dutch citizens whom the occupier believed to be anti-German. For these photographs, he was paid considerably more: five guilders each. But the work did not amount to much, the Bureau of National Security (BNV) concluded after the war.

On 12 July 1945, members of the BNV (the predecessor of the BVD, now AIVD, Dutch intelligence service) searched De Kok’s home at Vijzelgracht 27 and took several photos, which were handed over to “the Head of the Investigation Service” of the BNV. The whereabouts of these photos is unknown; they may still be held by the AIVD. The home of Van Poppel in Amsterdam-Zuid was also searched twice after the war, but the photos were not found at that time. Van Poppel, due to a traumatic neurosis resulting from an accident in 1932, was deemed too disturbed to stand trial. De Kok and Klarenbeek, however, were tried and sentenced to relatively short prison terms.

At the end of 2010, photographs taken by Bart de Kok surfaced during a renovation, together with photos belonging to Joseph van Poppel: dozens of family photographs and several from the war. The find also included Van Poppel’s chequebook and several blank notebooks belonging to the Jewish family that originally lived in the house: Martin Emil Levenbach, his wife Clara Fontijn, and their two daughters Emily and Eva. The daughters survived the war.

Lambertus Jasper (Bart) de Kok (Nijmegen, 6 September 1896 – 1972) was a Dutch photographer who worked during the Second World War. De Kok was a member of the NSB (National Socialist Movement) and took photographs of major and minor political events on behalf of the German occupying forces and the Amsterdam detective Willem Klarenbeek, which allowed him to photograph subjects forbidden to other photographers.

De Kok made a second print of every photograph without permission and stored these in the house of his acquaintance Joseph van Poppel in Amsterdam-Zuid. After the war, De Kok and Van Poppel were interrogated and the house was searched, but the photographs were not found. Photos that De Kok took in 1943 at Muiderpoort Station of a transport of Jews did become known. In 2010, during a renovation of the house in Amsterdam-Zuid, 250 of De Kok’s photographs were discovered, which he had taken in 1941 and 1942. These photographs show a confrontation during the February Strike, the removal of street name signs from streets with names of Jewish origin, and the seizure of diamonds from the mostly Jewish traders in the Diamond Exchange on 17 April 1942.

Sometime in 1941, Van Poppel introduced Bart de Kok to the Beauftragte für die Presse Boijes. Boijes instructed De Kok to take photographs of “all political events”: processions of the WA (the violent “order service” of the NSB) and scuffles between WA members and members of the Nederlandsche Unie. However, De Kok also took photographs at the request of a detective with the Amsterdam police, who had been seconded to the Crisis Control Service (CCD): Willem Klarenbeek. This man had himself photographed while frisking Jewish diamond traders, arresting Jews and taking them to the station on Doelenstraat, and rounding up Jews for the illegal slaughter of sheep and cows. As far as is known, Klarenbeek is the only “rogue” detective who had himself extensively photographed during his work.

De Kok received 50 cents per photo. He felt this was too little, but Boijes had told him that it was his duty as an NSB member to cooperate. He had to hand in the negatives, including those of the photos he did not sell to the Germans—undoubtedly without informing the occupier. What Boijes did not know was that De Kok delivered a print of every photo he took to Joseph van Poppel as well, including those he did not sell to the occupier. Presumably, therefore, there were three sets of photos: the ones found in De Kok’s home, the ones De Kok gave to Boijes, and the photos hidden by Joseph van Poppel, which have now been discovered in the building in Amsterdam-Zuid. What Van Poppel intended to do with the photos is unknown.

In total, De Kok took hundreds of photos. A limited number of these were already known, as noted above, such as a previously published photo of a CCD raid on the café of Wolf Hartlooper at Nieuwmarkt 15. New, however, are several photos of that same incident that were rejected by De Kok, presumably for photographic reasons. The other photos have not been published before. Altogether, the collection comprises some 250 photos, taken at dozens of (political) events.

In 1943, the occupier no longer had work for De Kok, he stated during an interrogation after the war. “I did this photographing until 1943. Then Boijes left for The Hague, and with that my work ended.”

In late 1944, De Kok, as an NSB member, received a compulsory call-up for the Landwacht (auxiliary police). He went to Zutphen for railway line surveillance and later to Harderwijk for the same work. No “atrocities” by De Kok are known from this period. It did emerge, however, that early in the war he had been sentenced by a German court to a fine of 100 guilders because he had lent a firearm to his “good” NSB friend Frans van Dam, who had committed a murder with it in the Amsterdamse Bos in “late 1941.” In April 1944, De Kok’s company was ordered to report to the SS, but he did not go. After the company was disbanded, he went to Amsterdam, but felt “outlawed” there as liberation approached. He then wandered around the Netherlands, in Utrecht, Hilversum, and The Hague, where he was arrested in July 1945 and interned in the Grand Hotel in Scheveningen.

In December 1945, De Kok was transferred to Amsterdam. The interrogations then revealed that De Kok had also worked for the Abwehr, the occupier’s counterintelligence service. De Kok photographed Dutch citizens whom the occupier believed to be anti-German. For these photographs, he was paid considerably more: five guilders each. But the work did not amount to much, the Bureau of National Security (BNV) concluded after the war.

On 12 July 1945, members of the BNV (the predecessor of the BVD, now AIVD, Dutch intelligence service) searched De Kok’s home at Vijzelgracht 27 and took several photos, which were handed over to “the Head of the Investigation Service” of the BNV. The whereabouts of these photos is unknown; they may still be held by the AIVD. The home of Van Poppel in Amsterdam-Zuid was also searched twice after the war, but the photos were not found at that time. Van Poppel, due to a traumatic neurosis resulting from an accident in 1932, was deemed too disturbed to stand trial. De Kok and Klarenbeek, however, were tried and sentenced to relatively short prison terms.

At the end of 2010, photographs taken by Bart de Kok surfaced during a renovation, together with photos belonging to Joseph van Poppel: dozens of family photographs and several from the war. The find also included Van Poppel’s chequebook and several blank notebooks belonging to the Jewish family that originally lived in the house: Martin Emil Levenbach, his wife Clara Fontijn, and their two daughters Emily and Eva. The daughters survived the war.

This picture of mr. Hammerstein was between the pictures Barbara donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Who was he? He lived at the same address as Barbara. This his card from the Amsterdam Archieve:

Name: Ludwig Ottomar HAMMERSTEIN.

Born: 22-11-1917 in Lämmerspiel, Germany.

Nationality: Alien.

Occupation: Physician.

Father: August Hammerstein. Born 01-07-1890 in Wiesoppende, Germany

Mother: Frieda Katharina Pauli. Born 02-02-1893 in Heldenbergen, Germany.

Married with Maria Johanna Elisabeth FAILE.

Born: 23-09-1913 in Amsterdam.

Marriage date: 07-01-1976 in Amsterdam.

Hammerstein lived in/at:

MUNICH

16-02-1946, Koningslaan 14HS, AMSTERDAM.

30-01-1970, Oranje Nassaulaan 11.

Born: 22-11-1917 in Lämmerspiel, Germany.

Nationality: Alien.

Occupation: Physician.

Father: August Hammerstein. Born 01-07-1890 in Wiesoppende, Germany

Mother: Frieda Katharina Pauli. Born 02-02-1893 in Heldenbergen, Germany.

Married with Maria Johanna Elisabeth FAILE.

Born: 23-09-1913 in Amsterdam.

Marriage date: 07-01-1976 in Amsterdam.

Hammerstein lived in/at:

MUNICH

16-02-1946, Koningslaan 14HS, AMSTERDAM.

30-01-1970, Oranje Nassaulaan 11.

Barbara with her mother in Amsterdam with in the background the first Dutch skyscrapper.

Family picture with in the background the same skyscrapper.

Ledermann family picture.

Barbara met Manfred Grünberg in 1944.

Both Margot and Anne Frank aswell as Barbara and Sanne Ledermann went to the 4e HBS in the Pieter Lodewijk Takstraat. They went by streetcar to get there. In 1957 the school was called the Comeniuslyceum. This lyceum merged in 1966 with the P.C. Hooftlyceum. They continued under the name Berlagelyceum.

Noorder Amstellaan 37.

Noorder Amstellaan 3 - 39. Gem. Archief Amsterdam.

Noorder Amstellaan seen from number 25. Gem. Archief Amsterdam.

Koningslaan 14, Amsterdam.

Suzanne Richardson and her mother Barbara Rodbell stand in front of the Martin Rodbell Nobel Medal Prize exhibit in Mason Hall, located on Johns Hopkins’ Homewood campus. Martin Rodbell, A&S ’49, received the Nobel Prize Medal in Physiology or Medicine in 1994. A gift of the Rodbell Family, it is now part of University Campus Collections, Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries.

'Suusje' © Anne Frank Museum.

weggum.com